Aliya to Israel

Who is eligible for Aliyah (immigration to Israel under the Law of Return)? Any Jew (defined as the child of a Jewish mother), child or grandchild of a Jew, or the spouse and minor children of the above, may make Aliyah, provided they haven’t converted to another religion from Judaism or pose a threat to the safety of the Israeli public. What does that mean in practice and how can one prove eligibility? The following article explains the process and limitations of Aliyah in-depth.

The Law of Return, and the right of immigration to Israel (aliya or aliyah) and citizenship for those eligible under it, has the status of a foundational law in Israel, even though it is not officially defined as such. The law generates much controversy, both because it grants clear preferential immigration status solely to Jews and their descendants, and because of internal debates among political and religious Jewish groups over the definition of who is a Jew, who should be allowed to make aliya on the strength of being related to a Jew, and who is not eligible to make aliyah to Israel.

It is important to remember that the law was passed in 1950, following World War II, only two years after the founding of the state of Israel. At that time, the need to provide refuge for Jews persecuted for their heritage throughout the world was more clear than ever before, and Jewish persecution was a reality whose horrors it was impossible to ignore.

The state’s concept of Judaism at that time was also more simplistic and secular (for example, the original Law of Return did not define a “Jew” as the child of a Jewish mother). Over the years, however, this concept has undergone frequent changes, and has received various legal expressions via court rulings and amendments to the law.

In this article, we provide a comprehensive explanation of the legal, essential, and technical aspects of the right to aliya, amendments and corrections made to the Law of Return, and of course, how one can make aliya to Israel.

The Law of Return: Its legislation and historical background

In 1950, when the Law of Return was proposed in the Knesset, Prime Minister David Ben Gurion introduced the law, saying:

“The Law of Return is one of the laws of the infrastructure of the State of Israel. It comprises a central goal of our State, the goal of the ingathering of the Diaspora. This law declares that it is not the State which bestows upon Diaspora Jews the right to settle in the State; rather, it affirms that this right is inherent in the very fact of being a Jew, as long as he desires to join in settling the land … Every Jew, as a Jew, has the historic right to return and settle in Israel, whether because he is deprived of his rights in a foreign land, or because his very existence is in danger, or because he is displaced and exiled, or because he is surrounded by hatred and contempt, or because he cannot live a Jewish life as he wishes, or because of his love for ancient tradition, Jewish culture, and the sovereignty of Israel.”

The Declaration of Independence of the State of Israel declared that:

“The State of Israel will be open for Jewish immigration [aliya] and the ingathering of the Exiles”.

These words clearly reflect the background and the basis for legislating the Law of Return. On the one hand, it was intended to bring Diaspora Jews back to Israel after their many years of exile, branded in the Jewish people’s memory: the exile that began as early as the destruction of the First Temple, On the other hand, the law sought to provide Jews, after long years of persecution, antisemitism, financial uncertainty, and fear, with the possibility to return to Israel as a place of refuge, the “Jewish state” that Herzl envisioned.

The Law of Return was passed, therefore, in 1950, and granted every Jew the right to make aliya to Israel. In the first years of the state, anyone who declared himself as a Jew and applied to make aliya to Israel was accepted without need for any additional proof. Likewise, there was no real need to specify that the son and grandson of a Jew were also eligible for aliya, since whoever declared himself a Jew obtained the right to aliya. Over the years, however, interpretation of the law changed a number of times in the wake of cases that stirred up public controversy, and the law itself underwent a number of amendments as well.

The question of who should be able to take refuge under the Law of Return, which seemed almost a given in the eyes of the lawmakers who originally passed it, changed as Judaism itself changed during the following years. Jewish law (halacha), which had not seemed relevant to Israel’s founding lawmakers, has since significantly affected Israel’s policy and jurisprudence.

Aliya policy before the founding of the State

The Zionist movement, from its very beginnings, was a movement which promoted aliya to Israel, and all the leaders agreed that one goal of the Jewish state-to-be in Israel would be to provide a safe place for Jews who wanted to make aliya to the land of the Patriarchs. But even within this movement, there were significant disagreements about aliya and its goals, the policy to be adopted regarding it, and where and how the movement should invest its resources for encouraging aliya.

Some leaders advocated bringing pioneers who would be trained in the professions needed in Israel, and only after these pioneers had “prepared the ground,” anyone else who wanted to make aliya to Israel should be allowed to come. Other leaders, in contrast, believed that anyone who wanted should be allowed to come, as fast as possible, partly to create a Jewish majority in Israel and partly out of concern for the Jews of Europe. Jabotinsky, for example, supported this view.

Thus the Zionist movement dedicated significant resources to locating Jews and bringing them to Israel over the years.

After the British established a highly restrictive immigration policy, and in effect began to block Jewish refugees from coming to Israel, the Zionist enterprise united with the entire Jewish settlement under the agenda of free aliya, in opposition to the British policy.

The Jewish settlement in Israel fought against the British restrictions, partially via illegal immigration ships, and this opposition, which became a full-blown policy adopted by the Settlement leaders, enabled the legislation of the Law of Return once the state was founded.

Who is entitled to make aliyah?

The right to aliya, which was originally intended for every Jew, as a Jew, has undergone legal transformations over the years. At present, the legal situation, according to the Law of Return, entitles the following categories of people to make aliya:

- Someone defined as a Jew by the Law of Return – i.e., the person’s mother is Jewish, and he or she does not belong to any other religion

- The child of a Jew

- The grandchild of a Jew

- The spouse of a Jew

- The spouse of the child of a Jew

- The spouse of the grandchild of a Jew

The question arises: if grandchildren of a Jew apply to make aliya to Israel with their family, can they make aliya together with their minor children? An adult great-grandchild is not eligible for the status of oleh,. but in the interest of not forcing the family to separate or abandon their attempt to emigrate to Israel, a special regulation was formulated for such cases, allowing grandchildren of a Jew who want to make aliya with their minor children to obtain legal status for them.

Likewise, it is important to note that under the Supreme Court ruling in the Isaacs case, even the child or grandchild of a Jew may not always be eligible for aliya if their Jewish parent or grandparent willingly converted to another religion.

To clarify your eligibility for aliya, you are invited to obtain legal consultation from our office.

Documents required to apply for aliya

To submit an application for aliya, you must furnish a series of documents; the Interior Ministry is authorized to request additional documents if they believe that any kind of doubt has arisen. The mandatory documents are:

Civil documents:

- The applicant’s passport

- The birth certificate of the applicant – if it is an original document and not a copy, in principle it does not require an apostille stamp. However, since many offices require an apostille stamp even on an original certificate, it is advisable to submit an original certificate, authenticated with an apostille stamp and translated by a notary public if it is not in English.

- A marriage license and birth certificates for the applicant’s children, if the spouse and children are also applying for aliya.

- A certificate of good conduct, also authenticated and translated, dated within three months of submitting the application.

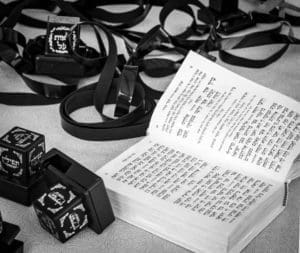

Documents to prove Jewishness:

- A letter from a community rabbi in their country of origin, from a list of rabbis recognized by the Interior Ministry, testifying to the applicant being Jewish, or to the Jewish ancestor on which the application for aliya is relying. For immigrants from the former Soviet Union – this letter is not required.

- For a Jew with a Jewish mother who is applying for aliya, it is advisable to bring the parents’ civil marriage certificate, which often indicates that the wedding took place in a synagogue or other Jewish framework; it is also possible to bring a copy of the parents’ Jewish marriage certificate (ketubah). This document must also be authenticated and translated.

- Someone applying for aliya on the basis of a Jewish father or grandparent must bring his or her parents’ marriage certificate, the father’s birth certificate testifying to his Jewishness, and sometimes even documents from the grandmother or grandfather, depending on what documents are already in the applicant’s possession.

- Often it is required to bring the death certificate of the Jewish father/grandparent, showing the place of burial in a Jewish cemetery.

- Any other document, pictures or evidence that can prove the applicant’s Jewishness.

Documents required in case of conversion to Judaism:

- In case of aliya on the basis of conversion, the applicant must bring an original giyur certificate – a ruling by the court where the conversion process took place.

- Likewise, an explanatory letter is required from the candidate for aliya, describing the conversion process that the applicant went through.

- A letter is required from the rabbi of the community to which the convert belonged before and after the conversion.

- A letter is required from the rabbi who performed the conversion, describing the process of the conversion.

Amendments to the law over the years and changes made in response to court rulings

As early as 1954, the first amendment to the law was already made. This was the addition of a restriction stating that the State was authorized to refuse aliya for a Jew with a criminal record if they might endanger the public.

In the early version of the Law of Return, there was no definition of who is a Jew; in the first years of the state, if someone declared himself a Jew, that was enough to grant him the right to aliya. Over the years, however, this question arose in various cases; those which reached the Supreme Court eventually brought about changes in the law itself.

Who is a Jew – the 1962 Rufeisen (Brother Daniel) Supreme Court ruling

The Rufeisen Supreme Court ruling is one case that dealt with the question of who is a Jew. Rufeisen was born to Jewish parents, and during the Holocaust he disguised himself as a Christian. Over time, he actually converted, not just to camouflage his Jewish identity, and became a priest by the name of “Brother Daniel”. He joined the Carmelite order and came to Israel in 1958 to serve as a priest in a monastery in Haifa. Rufeisen applied to make aliya, claiming that he was a Jew despite his conversion. He claimed that his Jewish heritage was not only religious but ethnic, and that he felt connected to the Jewish people.

The Supreme Court did not accept Rufeisen’s appeal. It is important to note that according to Jewish law (halacha), Rufeisen is considered Jewish, even though he converted to Christianity. Nevertheless, the Supreme Court ruled that someone who has declared his allegiance to another religion is not considered a Jew for the purposes of the Law of Return.

The Binyamin Shalit Supreme Court ruling

Another case is the Shalit Supreme Court ruling. Binyamin Shalit, a Jew, applied to register his children as Jews even though their mother was not Jewish. The Interior Ministry refused his application and he appealed to the Supreme Court. In this case the Supreme Court ruled in his favor, and ordered that the children be registered as Jews with “no religion” to be written in the section of “religion and nationality”. Although the court ruling dealt with the issue of registration and did not seem to touch the Law of Return directly, it in fact influenced the law significantly.

In the wake of these rulings and the ensuing public controversy, the Law of Return was amended in 1970, adding a definition for who is a Jew: “Someone born to a Jewish mother or someone who converted to Judaism (underwent Giyur), and is not a member of another religion.” In addition, the law was made to include spouses of Jews as well as their children and grandchildren (and their spouses).

Aliyah for spouses of Jews

It is important to note that despite the trend throughout the world, including in Israel, of liberalization regarding the concept of “partner”, the definition in the Law of Return still applies only to married couples. The issue has yet to be discussed in the Supreme Court, but it is likely that a case will come up in which a couple who have children together and are in a common-law marriage, will appeal to the Court, and the Court is likely to grant oleh status to the partner even if the couple is not married.

In according with the current state of the law, in this article we will discuss the right of someone married to a Jew to make aliya together with their Jewish partner, as well as the spouses of children or grandchildren of Jews.

Someone who is eligible for aliya and applies to bring his non-Jewish spouse with him is permitted to do so. It is even possible to do a “split aliya”, in which the one who is eligible emigrates to Israel alone first, and then the non-Jewish spouse follows.

Yet, there are certain conditions for a non-Jewish spouse to make aliya together with their eligible spouse, and we will discuss them in this article.

A couple married less than a year before applying for aliya:

A couple who got married a short time before making aliya must undergo a sort of “cooling period” before the non-Jewish partner can make aliya together with the eligible one. This is because such a scenario raises the suspicion of a fictitious marriage for the purpose of obtaining legal status in Israel. The regulation dealing with this issue is Regulation 5.2.0010 of the Population and Immigration Authority, called “regulation handling granting of legal status to couples in which one partner is eligible for aliya and the other not, who married less than a year before making aliya.”

Therefore, when a couple has been married less than a year when they apply for aliya, they will be required to prove the sincerity of their relationship, via documents such as: joint photographs, recommendations from family members and friends, correspondence between them, etc. The non-Jewish spouse will not be eligible for oleh status, but rather will receive a 5-A visa (temporary resident visa) for a year from the date of aliya.

At the end of the year, the couple will be invited to a detailed interview to re-examine the sincerity of their relationship. If the Interior Ministry is in fact convinced that the marriage is honest and not solely for the purposes of obtaining legal status in Israel, the non-Jewish spouse will receive oleh status. If the Interior Ministry is not convinced that the marriage is real, the visa will be extended for an additional year, and if there are still doubts after this second year, the file will be turned over to Interior Ministry headquarters for a decision.

Aliya for a same-sex married couple

Until 2014, there was no clear policy regarding aliya for same-sex married couples. In 2014, after many requests for guidelines from the Interior Minister, Minister Gidon Sa’ar issued a clear guideline to the Population and Immigration Authority, ordering them to view married same-sex couples as eligible for aliya just like other married couples. Thus he put an end to long years of discrimination.

Today, therefore, same-sex partners of Jews are eligible to make aliya on the basis of the same regulation and under the same conditions as married heterosexual couples.

Regulations regarding a great-grandchild of a Jew

Under the Law of Return, a great-grandchild of a Jew is not eligible for legal status in Israel, only a grandchild. Yet, the question arises: What happens when a grandchild of a Jew applies to make aliya with his minor children? The law does not grant legal status to the great-grandchild of a Jew, but on the other hand, it is clear that the law did not intend to cut off someone eligible for aliya from his or her minor children. Therefore, a special regulation was issued regarding the great-grandchild of a Jew who makes aliya together with his parent who is eligible for aliya.

The minor great-grandchild, who is under custody of his parents, themselves third-generation Jews, will not be eligible to receive Israeli citizenship under the Law of Return, but rather will receive temporary resident status – 5/A – as long as he meets the criteria set out in the regulation. The status will be extended every year for a cumulative total of three years. After three years, he can apply for Israeli citizenship. If he is still at minor at that time, he applies under Section 9 of the law; if he has reached the age of majority, he applies under Section 5.

The criteria for obtaining legal status are that the applicant is the great-grandchild of a Jew, and that his parents were recognized as eligible to make aliya under the law; likewise, that he makes aliya to Israel together with his parents. In order to obtain citizenship after three years, the great-grandchild must prove that his center of life is in Israel, together with his parents, even if he has reached the age of majority. In exceptional cases in which the parents left Israel during the process, the great-grandchild can continue the process via a legal guardian.

Widows of Jews

Since the Law of Return explicitly states that the right to aliya applies to the spouse, children, and grandchildren of a Jew, and even explicitly states that it is irrelevant whether the Jew in question is alive or not, or made aliya or not, the question arises: Is the non-Jewish spouse of a Jew who passed away still eligible to make aliya?

This question is discussed in the ruling on Supreme Court case 6247/04, Larissa Gorodetsky v. Minister of the Interior. Here it is important to note that in the framework of this appeal, the Interior Ministry did not claim that widows are not eligible to make aliya, and also the Supreme Court ruled unequivocally that the right to aliya as the spouse of someone eligible is reserved for widows and widowers of Jews and their descendants under the Law of Return itself.

However, the court addressed the question: Is this right reserved for widows and widowers of Jews for their entire lives? Or is this a limited right?

The petitioner, Larissa Gorodetsky, was married to a Jew and became widowed. Some twenty years later she remarried, to an Israeli, and after her second marriage did not work out, she applied for legal status as the spouse of an Israeli in her first marriage.

In this case, the Supreme Court ruled that the right is not absolute; although the right to aliya is reserved for widows and widowers of Jews, if they remarry, they lose that right.

Recently a district court issued a ruling, discussing a case in which a widow did not remarry, but carried on a long-term relationship and even bore another son to a non-Jewish father. In this case, the district court ruled that this was reason for the widow to lose her right to aliya on the grounds of being the spouse of a Jew. It is important to clarify, however, that this is not a Supreme Court ruling.

Therefore, the law practiced today is that the widow of a Jew is entitled to oleh status if she has not remarried, and it may be that she reserves this right even if she has additional children not from her marriage, as long as she has not remarried.

It is important to emphasize that everything said above applies only to widows of Jews when those widows are not themselves Israeli citizens, and not to widows who are in the process of obtaining Israeli legal status based on marriage to an Israeli rather than based on aliya.

Right to aliya for someone adopted by Jews

The right to aliya is based on the instructions of the Law of Return, which state that a Jew is someone whose mother is Jewish or someone who converted. The question then arises: Is this eligibility biological? Is this right reserved only for those children who are biological children of Jews? Or is there also an ethnic aspect to the eligibility, such that someone adopted by Jews is also eligible?

The regulation on granting legal status to a minor adopted by someone eligible for the Right of Return but who has not yet made aliya, number 1.8.2005, states that a minor adopted by someone eligible for aliya is also eligible for aliya, even though he is not genetically a Jew.

The Interior Ministry will check whether more than a year has passed since the adoption and if not, the adopting parent will have to prove the sincerity of the adoption, and convince the Interior Ministry that the adoption was not done in order to obtain legal status in Israel.

In other words, the Interior Ministry and Supreme Court rulings recognize that the Right of Return is not in fact just a genetic issue, but a right of a Jew and his descendants even if they are not genetic descendants – whether because it has an ethnic aspect, or whether because the adopted Jew has a right to be united with his family, genetic or not, in the State of Israel.

This interpretation fits the Supreme Court’s approach in the Shalit ruling, where the court ordered that someone with a Jewish father and non-Jewish mother should be registered as a Jew. However, this interpretation was not adopted by the Knesset, and in the wake of the Shalit ruling, the law was amended to define a Jew as the child of a Jewish mother. In the case of adoption, in contrast, the court’s interpretation was adopted as official policy, and the Interior Ministry registers adopted children of Jewish parents all the time, as long as no doubts arise regarding the sincerity of the adoption, and the family in question is making aliya for the first time.

In addition, there are reasons to suppose that someone who was adopted de facto –raised and educated in the bosom of a Jewish family but never officially adopted – should be eligible for aliya, as long as he can prove that he was indeed practically adopted while he was a minor.

Eligibility for aliya for a (biological) Jew adopted by foster parents of another faith

In 2004, Regina Bernick appealed to the Supreme Court, after her application for aliya was rejected by the Interior Ministry (9249/04). Regina was the biological daughter of Jewish parents, but was adopted by non-Jewish foster parents. After she filed her appeal, the Attorney General at that time was asked for his opinion on the legal issue of whether the adoption nullified Bernick’s eligibility under the Law of Return.

In the opinion, the Attorney General ruled that the Law of Return focuses on a person’s attachment to the Jewish people, and that this attachment is not severed if someone eligible for aliya is adopted by a non-Jewish family.

Following this option, Ms. Bernick was granted the status of an olah and full citizen of Israel. In various other cases where the Interior Ministry refused to grant oleh status to someone eligible for aliya who had been adopted by a non-Jewish family, the applicant was ultimately granted oleh status after filing an appeal with the Supreme Court.

Family members of Jews who are actively involved in another religion

As noted above, the Law of Return states that a Jew is someone who was born to a Jewish mother or who converted, but someone eligible for aliya is not necessarily Jewish. The law states that the rights devolve on children and grandchildren of Jews as well, but includes the qualification: “except for a person who has been a Jew and has voluntarily changed his religion.”

But regarding children or grandchildren of Jews, who were never Jews themselves, it is impossible to claim that they willingly converted, and sometimes they are practicing members of another religion. Thus, for example, someone eligible for aliya could be the child of a Jewish father and a Christian mother, be a devout Christian, and still be eligible under the law.

In the Supreme Court case 2708/06 — Steckbeck vs. the Interior Ministry — it was ruled, for example, that messianic Jews are eligible for aliya as relatives of Jews if they are children or grandchildren of Jews. If, however, they are Jews themselves – that is, children of Jewish mothers – they are not eligible. The Supreme Court ruled, in effect, that regarding aliya of someone related to a Jew but not himself Jewish, the religious faith of the applicant is not relevant.

In practice, however, the Interior Minister makes aliya very difficult for members of other faiths who are loyal to their faith. This is so even for those who are family members of Jews but not Jews themselves — the Ministry places many roadblocks in their way in order to deny them their right to aliya.

The authorities responsible for aliya, including the Jewish Agency, the Interior Ministry, and the organization “Nefesh b’Nefesh” (appointed by the Jewish Agency to be responsible for aliya from the U.S., including evaluating applications from U.S. Jews), ask aliya applicants if they are messianic Jews or other questions regarding Christianity. Whenever even the slightest suspicion arises that the applicant is a devout Christian, the aliya application is likely to be rejected, without relating to whether the applicant is the child of a Jewish mother or the child or grandchild of a Jew, despite the Supreme Court ruling.

Relatives of Jews with family members presently or formerly active in missionary activities also face problems in making aliya. The Supreme Court has already ruled on this (Supreme Court case no. 3820/10, Ze’ev Isaacs vs. the Interior Ministry) that someone who is active in missionary activities is not eligible to make aliya under the Law of Return as a family member of a Jew, since this activity directly contradicts the goals of the Law of Return.

“Not a member of another religion”

Section 4(b) of the Law of Return defines who is a Jew under the law, and states as follows: “For the purposes of this Law, “Jew” means a person who was born of a Jewish mother or has become converted to Judaism and who is not a member of another religion”.

The phrase “a member of another religion” is not the simple, unequivocal definition that it might seem. Someone who has publicly converted, as ruled in the Rufeisen Supreme Court case, after which the law was even changed to include this definition, is a very clear instance with no real doubt. However, there are quite a few instances in which the definition is not so clear.

The clearest example of this is the case of messianic Jews. Messianic Jews are a religious community, Jews by origin, who believe in Judaism and the Jewish bible but also in Jesus and the New Testament. The messianic Jews see themselves as entirely Jewish, just as Jesus viewed himself, but with an additional belief in Jesus as a messiah and the New Testament as a holy book. Note that many Messianic Jews are fully Jewish from an halachic point of view.

The Dolfinger Supreme Court case, 1979, first discussed the application of Eileen Dolfinger, a messianic Jew, to make aliya based on the claim that she was Jewish, under the Law of Return. The judges ruled that Christianity by definition is a religion that believes in Judaism and the Jewish bible, and its uniqueness is the added belief in Jesus, and therefore rejected the appeal. It was ruled that messianic Jews are not Jews and are not entitled to make aliya under the Law of Return.

A decade later, in 1989, the Supreme Court heard the Brasford case. Here too the case involved a messianic Jewish couple who applied to make aliya as Jews under the Law of Return. Despite the unequivocal ruling in the Dolfinger case, the couple insisted on filing an appeal to the Supreme Court to recognize them as Jews for the purposes of the Law of Return. The Supreme Court ruled that belief in messianic Judaism is de facto equivalent to converting to another religion, and on those grounds the appeal was rejected.

An appeal filed in 2017, the Supreme Court case of Timothy McKainy, established this ruling in our day as well. In a brief verdict, the Supreme Court stated that the law anchoring the previous decisions, Dolfinger and Brasford, still held.

Yet, it is important to note that messianic Jews with a Jewish father and non-Jewish mother can obtain legal status under the Law of Return as relatives of Jews. This is because they are not themselves halachically Jewish, and therefore it cannot be said that they “converted” to Judaism.

The court rulings clearly point to a secular and not religious definition of who is a member of another faith. It integrates theological criteria, as in the Dolfinger ruling, with a definition under which someone who is not considered a member of another religion in the eyes of the average Jew is still a Jew.

Therefore, the current legal situation regarding messianic Jews is such that messianic Jews cannot make aliya on the basis of being Jewish. They are not eligible for oleh status, since they are considered members of another religion, or alternatively – that they willingly converted. Family members of Jews, however, even if they are messianic Jews, are eligible to make aliya, as long as the Jewish family member has not cut off his own ties to Judaism.

“Breaking the chain of Judaism”

These legal precedents, which in fact expanded the stated restrictions in the Law of Return, reached their height with Supreme Court case 10535/09, Anon. vs. the Interior Ministry. In this appeal, a Muslim woman, grandchild of Jews, and Jewish herself by halacha (her mother being Jewish), applied for olah status. The appellant’s mother was Jewish but had married a Muslim man, converted to Islam, and raised her children as Muslims.

The Supreme Court rejected a request to hold an additional hearing on this verdict, ruling that the mother’s conversion was considered “breaking the chain of Judaism”. The rationale behind this rejection was that the Law of Return is intended to allow Jews and their families to make aliya, and when the Jewish parent/grandparent loses their right to aliya due to conversion, their descendants also lose that right.

Proposed amendments to the Law of Return that did not pass

Over the years, many amendments and corrections have been proposed to the Law of Return. Many believe that the law’s purpose is bring to Israel only those with real ties to Judaism, Jewish tradition, and Jewish leaders. Some believe that only people who are halachically Jewish should be allowed to make aliya, which would include, for example, those who had converted to another religion. Others believe that anyone who is a child or grandchild of a Jew, or even a great-grandchild, should be eligible for aliya.

The right to aliya is a right that stirs up much emotional controversy, touching the core of Israeli society: defining who is a Jew and therefore who has the almost-automatic right to become an Israeli citizen, and it raises strong feelings among everyone involved. Accordingly, it is no wonder that many amendments and corrections to the Law of Return have been proposed, by various means.

A proposal that has frequently arisen, from the 1990s on, is to cancel the aliya right of the grandchild of a Jew. This proposal has a number of variations; some have proposed cancelling the right entirely (for example, in 2001); others have proposed limiting this right such that grandchildren could make aliya only together with the Jewish grandparent, in order to encourage aliya. In recent times as well, in 2020, a proposal was raised to cancel the right of return for the grandchild of a Jew, although it was rejected out of hand.

The opposite was also attempted, in 2005, with a proposed amendment that would give aliya rights to a great-grandchild of a Jew as well as to a grandchild. This proposal, however, was rejected at a very early stage.

In 2003 the Knesset heard a proposal to recognize Anusim (descendant of Jews forced to convert away from Judaism) as fully eligible for aliya. Various proposals regarding the law’s definition of “conversion” were also rejected.

In the end, the law remains as it has been for many years, due to various forms of resistance to any change, with all population groups, represented in the Knesset by various political parties, opposing the changes, each for its own reasons.

Since there is no consensus in Israeli society regarding who should be recognized as eligible for aliya, the definitions remain as they were the last time there was majority support among the lawmakers to amend the law – in the 1970s.

Aliya on the basis of conversion

The status of various non-Orthodox Jewish communities is a controversial subject in Israeli society, stirring up powerful feelings.

Despite Supreme Court rulings on this issue over the years, the right to aliya on the basis of conversion is still granted almost exclusively to converts who have gone through Orthodox conversion. Though the Supreme Court has ruled repeatedly that a non-Orthodox conversion is enough (the Miller Supreme Court case), in practice the Supreme Court generally returns the question to the Knesset time after time, rather than ruling on the validity of reform or conservative conversion as a whole.

Thus in the Goldstein case, the Supreme Court ruled that there is no legal basis for the Orthodox monopoly on the conversion recognized for aliya to Israel. However, the Court still referred the matter to the Knesset for legislation.

After years of controversy, a dedicated committee was convened which took years to produce results. Finally it submitted proposals by which the Jewish status of Orthodox converts would be retained, but a conversion school would be established to include representatives of other streams – Reform and Conservative – in Judaism.

For a certain period, the Interior Ministry recognized people who converted with Rabbi Druckman, who did not obligate the converts to keep Torah and mitzvot fully during the conversion process, as eligible for aliya. But after a judge in the Rabbinic Court overwhelmingly cancelled all these conversions, the Interior Ministry went back to implementing its previous policy, recognizing only Orthodox conversion for purposes of aliya. That is, there is a specific list of rabbinical courts in Israel and even worldwide (even though this is not entirely in accordance with the Supreme Court ruling) whose conversion is recognized for the purposes of aliya.

This situation creates many problems; thus, for example, in certain countries there is no religious court at all that is recognized for conversion, and there are long waiting lists for conversion in recognized courts, sometimes involving years of waiting.

In n any case, anyone who is not a citizen or permanent resident of Israel is entirely unauthorized to convert in Israel without a special permit from the Prime Minister’s office, which operates an exceptions committee to approve conversions in special cases. Despite Supreme Court rulings on the issue, at present it is still difficult to obtain legal status on the basis of conversion other than that sponsored by the state, even if the conversion is strictly Orthodox.

Conversion in Israel: Exceptions committee and recognition of various conversions

As a rule, the conversion system in Israel serves only those who have Israeli citizenship or permanent residency; it does not serve people who do not have that status. Therefore, for a candidate with any other visa to undergo conversion in Israel, and be eligible for legal status on the basis of this conversion, he or she must go through a special exceptions committee.

To apply to the committee, there are prerequisites. First of all, the conversion applicant must hold a regular tourist visa (2B) or a temporary resident visa (5A) – and the latter only if he has held a 5A visa for over a year.

After submitting the application, the candidate will be invited for an interview with the committee, in which he will be asked why he wants to undergo conversion specifically in Israel. He will also be asked additional questions intended to verify the sincerity of his desire to undergo giyur in Israel. The candidate must come to the interview with official documents (such as: a certificate of good conduct from abroad, verified and with an apostille stamp; a summary of his registration in the Interior Ministry) as well as a curriculum vitae in Hebrew, an application letter from the candidate explaining why he wants to convert, his connection to Judaism, a short summary of his personal status; profession, family in Israel and abroad, spouse, etc. In the letter, it is important to specify any connection with various Jewish communities, connection with religious Jewish families in Israel or abroad, etc.

If the application is approved by the committee, the candidate can register for a conversion course in Israel, but only in one of the places recognized by the committee. At the end of the course, there will be an additional interview with the conversion candidate, after which it will be decided whether he can already undergo judicial conversion or whether he must continue studying.

After obtaining the second permit, the candidate must obtain a conversion permit from the rabbinical court, and then an official conversion permit is issued by the Prime Minister’s office.

At present, conversion performed in Israel is recognized for aliya only if it is done in this framework. Other forms of conversion are not recognized by the committee, and thus are not recognized by the Interior Ministry and cannot serve as a basis for aliya.

Conversion abroad

Conversion outside of Israel also exists in various types, Conservative, Reform, etc. This article only deals with conversion that is recognized for the purpose of aliya.

For the conversion to be recognized for the purposes of aliya, it must meet several criteria:

First, the conversion must be performed in the framework of a recognized Jewish community abroad.

Second, the aliya candidate must have converted in the framework of an organized, recognized conversion program in one of the recognized religious courts or communities. There is a list of religious courts and rabbis who are authorized to approve such a conversion at the end of the process, and it is important to make sure that the conversion program in which you are participating meets this criterion. The program itself must be for a period of at least nine months. However, if the program is shorter, it is possible to overcome this problem if the organization performing the conversion provides confirmation that the number of hours in which the candidate participated was more than 300.

Third, it is important to note that when the conversion was performed a long time ago, the Interior Ministry is authorized to require an up-to-date letter regarding the candidate’s participation in the community or a conversion permit. Likewise, in the case of doubt about the sincerity of the conversion, the Interior Ministry is authorized to request any document which will help resolve the doubts before approving aliya.

If less than nine months have passed since the conversion abroad, and the aliya candidate wants to come to Israel nevertheless, it is possible to do so. In such a case, the applicant will receive a temporary resident visa (5/A). He can then participate in a community in Israel, and submit a letter regarding his participation in that community after nine months in order to receive aliya status.

Court rulings concerning various conversions

The right to aliya for someone who converts is determined by the Law of Return itself. However, the law did not specify the details of this definition, something that has led many legal issues to reach the Supreme Court, which until recently was the relevant court for the issue of aliya.

In practice, several government decisions have granted authority for conversion solely to the Orthodox conversion system. The immigration authorities and the government are interested in causing difficulties for converts, given the fear that conversion is an effective means of obtaining legal status in Israel and therefore conversion is not always sincere and honest. In the process, they also cause great difficulties for people who sincerely desire to convert.

The relevant government decisions are Decision 3155 (2/ayin) from 14.2.08 and Decision 3613 from 4.7.1998, both of which deal with conversion performed in Israel. However, such a fundamental issue should be regulated by actual legislation, as the Supreme Court has ruled on more than one occasion.

Supreme Court decision 2597/99, Toshbeim v. the Interior Ministry, stated for the first time that a conversion performed by a recognized Jewish congregation abroad should be recognized for the purposes of the Law of Return. According to the ruling, Conservative and Reform congregations were included in the definition of an active, recognized Jewish congregation, solely for the purposes of the Law of Return. In the framework of this court ruling, it was also clarified that the State has the right and obligation to determine which Jewish congregations are recognized, as well as setting additional conditions to prevent misuse of this law. Such conditions have indeed been set.

In the Supreme Court decision 7625/06, Margarita Regocheva v. the Interior Ministry, the Court ruled that there is no justification for the government’s approach, by which only Orthodox conversion is considered conversion for the purposes of the Law of Return; it is enough that the conversion is performed in a solid, recognized Jewish congregation. The Court determined that, although the appellants converted under a private conversion and not a state one, they should receive oleh status.

This court ruling set off a storm of controversy, and a memorandum of law was submitted in May 2017 with the intention of bypassing the Supreme Court’s ruling on this issue. The State Conversion Memorandum of Law was passed almost unanimously by the Minister’s Legislative Committee. However, Minister Sofa Landever filed an appeal of this decision, and thus the legislation on the issue was brought to a halt. Subsequently, another committee was formed: the Nissim committee, whose job was to submit recommendations to the government on this issue.

This court ruling set off a storm of controversy, and a memorandum of law was submitted in May 2017 with the intention of bypassing the Supreme Court’s ruling on this issue. The State Conversion Memorandum of Law was passed almost unanimously by the Minister’s Legislative Committee. However, Minister Sofa Landever filed an appeal of this decision, and thus the legislation on the issue was brought to a halt. Subsequently, another committee was formed: the Nissim committee, whose job was to submit recommendations to the government on this issue.

The committee’s recommendation took an extremely lenient stand towards converts, and led to the proposed State Conversion Law in 2018, introduced by MK Yehuda Glick. However, the proposal aroused great resistance within the ultra-orthodox faction, and therefore it never actually reached the floor of the Knesset.

Therefore, the legal situation today is that despite the Regocheva Supreme Court ruling, the Supreme Court chastised authorities who did not implement the ruling and wrote that: “It will be said immediately that we did not find cause to avoid discussing the substance of the petition before us. The fundamental decision in matters of Orthodox conversions not conducted through the state conversion system was given in the Regocheva case, more than two years ago. The respondents are obligated to act in accordance with this decision, without relying on future legislative processes…”

Since the issue has not yet been regulated by legislation because of the fierce controversy surrounding it, the current situation is that various types of converts are not comprehensively recognized for the purposes of obtaining legal status in Israel. Instead, each case is discussed on its own merit when they reach the court.

Restrictions on aliya

The Law of Return includes a number of restrictions: meaning, cases in which someone does not have an absolute right to aliya even if their Judaism is not in doubt.

Section 2B of the Law of Return states that:

“An oleh’s visa shall be granted to every Jew who has expressed his desire to settle in Israel, unless the Minister of Immigration is satisfied that the applicant:

- is engaged in an activity directed against the Jewish people; or

- is likely to endanger public health or the security of the State.

- possesses a criminal record and is likely to endanger public safety.

In this article we will discuss what is covered by each of these restrictions, and when it is legitimate to reject an aliya application on the basis of one of them. Yet, it should be noted that the first two restrictions are fundamental restrictions which are used very rarely, and therefore we will focus primarily on the third one, which is the most relevant of the three.

Rejection due to actions against the Jewish people/threat to state security

These restrictions, as of today, are in principle only; there is no known case in which a court has ruled in practice that an oleh visa should be refused due to these restrictions.

Reading the Knesset’s words during the legislation on “operating against the Jewish people,” it appears that this section was highly controversial, and that the Knesset took care to word the law in the present tense in order to grant a sort of clemency to someone who had operated against the Jewish people in the past but had ceased such activity. However, it is also important to note that the section was added in the shadow of World War II. It appears that the legislators themselves had difficulty believing that there would be a case in practice where a Jew would act against the Jewish people, and it is no surprise that this section of the law has been applied sparingly, if at all.

Yet, in light of the Interior Ministry’s recent policies, it is impossible to rule out a situation where this section might be applied. Although the legislators were aware of the problematic nature of the wording when they formulated it, and one of the speakers even commented that it is important to explain that actions against the Jewish people cannot be criticism of actions by the state or by Jews, the number of incidents that have taken place in recent years indicate a significant chance that this section will be applied in the future.

Thus, for example, an American Jew, a journalist who constantly criticized Israel’s policy regarding the Palestinians, was detained for interrogation at Ben Gurion Airport, and was released only after he hired legal counsel. He was questioned at length about his political leanings and his intentions to participate in a demonstration, as well as his ties to various organizations.

Likewise, in recent years, we are witnessing more and more refusals to allow entrance to human rights activists from various countries or political activists, under the Entrance to Israel Law but not under the Law of Return. The most famous of these are the ban on entering Israel for a human rights activist, Omar Shakir, for the fact that the organization’s activities include reports accusing Israel of war crimes, as well as other harsh criticism of Israel’s policies; and a ban on entrance to a student thought to be active in an organization criticizing Israel.

Refusal due to a public health hazard

This section is intended to prevent the immigration of those carrying infectious diseases, who are likely to endanger the health of the general public, not patients with any other diseases. Officially, there is no documentation of a refusal on public health grounds, but when filling out the Population and Immigration Authority forms, an aliya candidate must declare that he does not suffer from mental illness/addiction to hard drugs or alcohol/tuberculosis/any disease that is likely to endanger public health or welfare.

It should be emphasized that even in the form itself, the formulation of the question goes beyond the language of the law, in requiring the candidate to declare himself free from any disease that would endanger “public welfare” and not just public health, without any real justification.

This means that in practice, even though there is no legal justification for it, Population and Immigration Authority officials see addiction to hard drugs or alcohol, as well as mental illness, as part of this section, without any legal or judicial foundation.

The stigma against various types of mental health system survivors is a long-standing, difficult issue, which seriously harms mental health system survivors and their families. The survivors themselves are often forced to hide their illness due to this stigma, and many even avoid seeking treatment out of fear of being thus labeled, and the implications of such a label, whether social or entirely formal, such as the right to make aliya.

The aliya questionnaire does not define a time frame, such that even someone who suffered briefly from post-trauma, due to one-time traumatic event, for example, even if it occurred many years ago, apparently would be forced to declare this fact.

In practice, this issue has not yet been heard in the Supreme Court. When someone states on the aliya form that they are or were suffering from a mental illness, a torturous journey begins. This is mainly expressed by the application process being dragged out, forcing the applicant to wait months or even years for an answer. The applicant is also often required to submit documents over and over again, from psychiatrists or other professionals (even if he has not required their services for many years), all without result, until he either gives up or seeks assistance from the court.

The involvement of legal counsel can sometimes help the applicant before he turns to the court. But as noted, there is no real jurisprudence on the issue: in practice, appealing to the court on account of the delay does not get heard, since the Population and Immigration Authority ultimately does not refuse aliya applications on these grounds – something that leads to closing the appeal without ever discussing a real refusal on the grounds that the applicant is dealing with a mental illness.

In more than one appeal on this issue filed from our office, as well as letters to the various Interior Ministry offices asking for a solution to similar requests, it is has been claimed in detail that there is no legal basis for including any question regarding mental illness, when deciding whether or not to grant an oleh visa.

This policy is doubly hard to understand when examining it from the perspective of the Law of Return itself, given that one of its main goals is to provide a political home for persecuted Jews from various places in the world. It is clear that such persecution may have harsh psychological consequences; there is no doubt that many of the immigrants who arrived in Israel after surviving the horrors of the Holocaust suffered from post-trauma or other mental health issues. No one can doubt that this section in the Law of Return is not intended to ban mental health system survivors from entering Israel, if only due to the understanding that many of the Holocaust survivors would not have met this criterion themselves.

It is impossible to ignore the fact that even if an official refusal is not given due to a declaration of mental illness, in practice the Interior Ministry places a major stumbling block before many mental health system survivors with its unacceptable policy of endless red tape and piling up infinite difficulties for the applicants, sometimes following a one-time mental health event that occurred many years earlier. This policy reflects the long-standing stigma, but it has no place in a modern, normally functioning country, and it should have been brought to an end long ago.

Rejection due to a criminal record

The last restriction set out by Section 2 of the Law of Return is the restriction which sees the most use. Anyone applying for aliya must present the Population and Immigration Authority with an up-to-date certificate of good conduct and thus, in practice, any criminal record can be a reason for rejection under this section.

The language of the law states explicitly that an applicant will only be refused an oleh visa if his criminal record represents a danger to public welfare. The rationale behind the exception in the law is to protect the Israeli public’s right to live in peace and prevent criminal Jews from exploiting the Law of Return to escape prosecution in their own countries, and most of all to bar entrance to Jewish criminals who have made crime their way of life.

Thus it is written in Supreme Court decision 6624/06, Peshko v. the Interior Ministry:

In the Malevsky case, Justice Zamir (pp. 697-698): “Although, as Justice Zussman pointed out, the rule is that every Jew is entitled to make aliya to Israel, and the Interior Minister’s authority to deny an oleh visa to a Jew who has a criminal record which could endanger public welfare is an exception to the rule, and therefore, ‘It should not be interpreted as broadening’ (Supreme Court decision 94/62 Gold v. the Minister of the Interior, 16 1846, 1855), the exception is not to be interpreted such that it nullifies the purpose of the exception. The State of Israel is not obligated, and generally does not even wish to, serve as a country of asylum for a Jew who has made a life of crime. The Israeli public’s right to peace and security should not fall victim to the right of such a Jew to make aliya.”

In a series of rulings, the Supreme Court determined which considerations may be used to decide whether someone has a criminal record that represents a danger to public welfare.

The first factor taken into consideration is the severity of the crime. The more severe the crime, the more likely the court is to confirm a rejection of an oleh visa application. This is not the only consideration, however; as noted, the law states that the criminal record must represent a danger to public welfare in order for the rejection to be valid. Therefore, other possibly mitigating factors are taken into account: for example, if a long time has passed since the crime was committed, and no more crimes have been committed in the intervening period, this reduces concern for harm to public welfare; if the criminal underwent full, comprehensive rehabilitation, expressed regret and changed his way of life, this is also a factor in the applicant’s favor which must be taken into account.

The rejection must reflect a reasonable chance that the applicant will continue his criminal activities in Israel, and as such, it does not necessarily depend on a conviction. Thus, for example, in the 1970s, the Supreme Court heard the case of Meir Lansky, an American citizen who was convicted of various gambling crimes, and according to the claims, was linked to organized crime in the U.S. After Lansky arrived in Israel, an indictment was issued against him in the U.S. for other acts of organized crime, for which he had not yet been convicted when his aliya application was rejected.

The Supreme Court ruled that even though Lansky had not yet been convicted in the U.S., the sum total of indictments against him, together with past convictions, constituted adequate indication to justify rejecting his aliya application.

In Supreme Court decision 8292/11, it was ruled that despite the fact that 28 years had passed since appellant Padchenko’s crimes were committed, the fact that the appellant committed repeated sex crimes in severe circumstances and did not present any indication – except the amount of time that had passed – that he no longer represents a danger to the public, the appeal for approval of an oleh visa would be rejected. This shows that real rehabilitation and regret, documented by an appropriate professional opinion, bear more weight than the passage of time.

In contrast, in a 2020 opinion by the Administrative Affairs Court, administrative appeal n# 40293-01-20, the judge ruled that despite a criminal record in Germany and additional crimes that were transferred to Israel, a ruling was made, with the agreement of both sides, that the appellant would be given an additional “trial” year, after which, if no additional crimes were committed, he would be eligible for oleh status.

In any case of a criminal record, even a minor one, one must assume that the process will be considerably drawn out, and the Interior Ministry will require the applicant to attend additional interviews. Therefore, in a case of a criminal record, even if minor, it is very important to obtain appropriate legal counseling before submitting the application.

Citizen immigrant / returning minor

Someone who already has Israeli citizenship can sometimes be eligible for oleh benefits and can obtain oleh status.

A citizen immigrant is someone who was born abroad to an Israeli parent and would be eligible for oleh status under the Law of Return, if he was not an Israeli citizen to begin with. Someone who immigrates to Israel and meets this definition is eligible for oleh status, even though he is already an Israeli citizen.

Under the law, a child who is born abroad to an Israeli citizen receives Israeli citizenship on account of his parents, even if he never visited Israel. It is important to note that this status is not transferable to the next generation; Israeli citizenship on the basis of birth is granted only for one generation.

Yet, obtaining oleh status is not a trivial matter, and carries with it significant benefits: assistance from government offices, tax benefits, etc. According to Population Authority regulations, Israeli parents must report the birth of a child abroad within 30 days of the birth, and register the infant as an Israeli citizen. If the child is born outside of marriage or is not registered in time, a paternity claim may need to be made before the registration can be approved. This is also true for any other case where the child’s identity as a child of an Israeli may be in doubt.

It is important to note that benefits are granted to a new immigrant according to the date of arrival in Israel. Accordingly, if someone comes to Israel for an extended period and only afterwards obtains oleh status, he or she may lose these benefits.

A returning minor is someone who left Israel after obtaining citizenship (either as an immigrant or as someone born to Israeli parents), before the age of 14, and returned after the age of 17. During the period between leaving Israel and returning to it, the minor must spend at least four years abroad, a minimum of eight months in each calendar year, in order to be eligible for oleh status. This is all, of course, on the condition that he is eligible for return under the Law of Return.

A citizen immigrant or a returning minor must submit an application to receive their oleh rights when they apply to return to Israel permanently. If they are eligible for an exemption from IDF service, it is important to arrange this exemption when they reach the age of induction, if they are still abroad, in order to avoid future problems.

Although a prolonged stay in Israel may prevent receiving oleh rights, there are a few reasons for which it is permitted to stay in Israel for a long period without losing the right to receive the status of returning minor or citizen oleh, including:

- Staying in Israel for less than 4 months in each calendar year.

- IDF service.

- Staying in Israel for a few months before and after IDF service.

- Studying for a year or less in a recognized Israeli educational institution.

- Studying and residing in Israel in the framework of a program like “Masa” and others, for those eligible to return.

These rights will be canceled for someone who received assistance as an oleh in the past. They will also be canceled for someone who resided in Israel for an extended period before applying (someone who resided in Israel for up to three years can still receive partial benefits, while someone who resided in Israel for five years or more is not eligible for any benefits).

Finally, an Israeli resident who returned to Israel after an extended stay abroad is considered a “returning resident” and is also entitled to certain benefits.

Revocation of aliya status

When someone made aliya and received Israeli citizenship, under the Law of Return, and then it was discovered that the aliya was done on the basis of false information, or forged documents, the Interior Minister has the right to revoke the citizenship which was obtained under false pretenses.

Section 11(c) to the Citizen Law states that “The Interior Minister is authorized to revoke Israeli citizenship from someone if it is proven to his satisfaction that the citizenship was acquired on the basis of false information.” This section is primarily relevant for immigrants to Israel.

In the case of aliya of a newly married couple, they must wait a year to be sure that the marriage was not solely for the purposes of obtaining legal status in Israel. However, if the issue is aliya that was given on the basis of forged documents or false information, sometimes a long time has passed since the status was granted, thus creating additional legal problems.

First of all, it is important to note that the Interior Ministry makes use of the services of various bodies, such as “Netiv” or “Nefesh b’Nefesh”, which verify the authenticity of the documents submitted in various regions of the world. Over the years, the authorities’ ability to check has also improved, including regarding false information. With the rise of social networks and the Internet, the possibility of obtaining information on aliya candidates is greater, so at present such cases are increasingly rare.

Revoking aliya on the basis of forged documents: It is clear that if the documents submitted for aliya are found to be forged, there is clear justification for revoking the citizen status. However, as noted, such cases are not common, given that today there are ways to clearly verify the accuracy of documents, such that forgery of documents is rare.

Regarding false information, however, the situation is different. When someone makes aliya to Israel, he must make declarations regarding a number of things: his marital status, his medical background, his religious faith, etc.

Thus, for example, if someone of Jewish extraction converted to Christianity, or his mother converted, and he did not declare this when applying for aliya, his citizenship could be revoked if this is discovered, even if many years had passed.

In a case where someone declared that he did not belong to another faith, but did not state, for example, that he was a messianic Jew, this is also false information, on the basis of which his citizenship can later be revoked.

When someone’s citizenship is revoked, this also means revoking the right of a minor who obtained his status together with his parents. However, there are cases in which many years have passed, the children are already grown, and they were unaware that their citizenship was acquired under false pretenses. Many times in such cases, there are indirect ways to preserve the children’s status as citizens, or they are ultimately granted the status of residents. The Supreme Court has not yet ruled on the question of whether the recipient of citizenship must be aware of dishonesty or false information in order for his citizenship to be revoked.

It should be noted that, given that the right to citizenship carries great weight, the court imposes an equally heavy obligation on the Interior Minister to produce evidence justifying revocation. The Interior Minister must rely on substantial proof in order to revoke citizenship.

Aliya via the Jewish Agency

Anyone who wants to apply for aliya while still abroad must, according to regulations, do so at an Israeli embassy consulate. In practice, however, the authority to handle such applications is given to the Jewish Agency throughout the world. The Jewish Agency is sometimes assisted by additional organizations, detailed below.

To apply through the Jewish Agency, a full application must be submitted, with all the required documents scanned, and sent by email to the relevant branch of the Jewish Agency. After the Jewish Agency checks the application and confirms in principle that the applicant is Jewish or that he is eligible for aliya, a meeting is arranged with the “shaliach” of the Jewish Agency. In this meeting, the candidate must present all the original documents which have been sent by email, and they will be examined.

At this meeting the candidate will undergo an interview in which he will be asked about his application and his desire to immigrate. If any doubts arise regarding the application, he will be asked about them.

If the aliya application is approved after that, the immigrant will be issued a certificate of eligibility, and when he arrives in Israel, he will be given an oleh certificate at Ben Gurion airport. After that, he will be invited to receive an identity card.

Aliya via other organizations in various countries

In various countries, there are organizations placed in charge of accepting and checking aliya applications before they are passed on to the Jewish Agency or the Interior Ministry.

At the beginning of this section, it is important to emphasize that many times, organizations present themselves as assistance organizations for olim and appear to represent the potential immigrants’ interests, but in practice one must understand that these organizations are sort of branches of the Interior Ministry and the Jewish Agency throughout the world. Therefore, you must behave with these organizations exactly as you would with the Interior Ministry or the Jewish Agency; in any case of doubt or irregularity, their interest is not necessarily in clarifying the doubt or problem. Instead, many times, their interest is in getting the application rejected.

Nefesh b’Nefesh

The organization Nefesh b’Nefesh deals with submitting aliya applications from North America — the U.S. and Canada. It specializes in evaluating applications from these countries. Those who submit their applications via this organization must fill out an online application on the organization’s website. The application includes many questions regarding the candidate for aliya. Likewise, those eligible under the Law of Return are required to upload copies of all the requested documents. Then they are invited to a meeting in which they must present the documents themselves to a representative from Nefesh b’Nefesh. If the application is approved by this representative, the case is transferred to the Interior Ministry, which issues an aliya permit. Anyone making aliya through Nefesh b’Nefesh receives assistance in the aliya process, and receives an Israeli identity card on landing at Ben Gurion airport.

Netiv

Netiv is an organization that specializes in evaluating applications and official documents of those making aliya from Eastern Europe: Russia, the Ukraine, Romania, etc. Someone applying from one of these countries does not submit the application to Netiv, but to the Jewish Agency, which refers the applicant to a document check and short interview with Netiv. After obtaining Netiv’s confirmation that the documents are in order, the process continues with the Jewish Agency.

Beyond these organizations, the Jewish Agency itself has various departments specializing in handling different countries: a department for olim from France, and another one for olim from South and North America. Each department specializes in recognizing the recommending rabbis and the known and recognized Jewish communities in those countries, in order to meet the needs of olim from there.

Aliya from various countries

Immigration to Israel is literally an ingathering of the exiles. Every year, olim arrive from dozens of countries throughout the world. Since the state of the Jewish community is unique for each country, requirements of the oleh may differ somewhat among countries.

Thus, for example, immigrants from the former Soviet Union are not required to present a letter from a community rabbi. This is due to the understanding that for many years, there was no real community religious life under the Soviet regime. Thus, Jews from these countries are sent to an evaluation which relates more to their ethnic Jewish background than their belonging to a Jewish community.

Immigrants from France are required to bring a certification of the applicant’s Jewishness from the Paris beit din.

However, some people of Jewish extraction live in places where no organized Jewish community can be found; thus, for example, immigrants from countries like Peru cannot prove their Jewishness in practice, given that the communities there are very small and there are no rabbis there who are recognized by the Interior Ministry. Therefore, they must prove their Judaism in other ways.

It is important to understand that in practice, the law does not require bringing a letter from a rabbi to prove one’s Jewishness, and this can be proved in other ways; one can bring photographs of the gravestone of the Jewish grandfather and birth certificates proving the applicant’s link to him, as well as various other means if necessary. Many times in such cases, an appeal to a court is necessary before oleh status is granted.

Our office specializes in the Interior Ministry’s various demands of immigrants from around the world. We can guide applicants regarding the individual requirements for each country.

Immigration from Russia

In the Communist Soviet Union, religious organizations and institutions were generally outlawed, and thus most of Soviet Jewry became secular over this long period. Anyone who maintained a Jewish way of life did so in secret because of persecution at the hands of the regime.

This situation also led to many mixed marriages, as well as creating significant difficulties for Soviet Jews and their descendants when they try to prove their Jewish heritage.

It is important to understand that despite this, anyone who was of Jewish extraction in the Soviet Union often suffered from antisemitism and repeated harassment. Their Jewish identity was thus branded in them, such that they saw themselves as fully Jewish. Many of them were shocked and hurt, therefore, when they immigrated to Israel and discovered that they were not considered halachically Jewish due to being the child of a Jewish father but not a Jewish mother, or because they had difficulties proving their Jewish extraction.

In light of this, immigrants from the Soviet Union at present are not required to prove their Judaism in practice. When they apply for aliya, they declare their Jewishness, and then the application is turned over to the organization Netiv. This organization checks the documents submitted to make sure they are in order and verifies that they are real, as well as checking the applicants’ Jewish heritage in various ways. To do so they rely on various sources which are unlike those used for checking potential immigrants’ Jewishness in other countries, given the evidentiary difficulties of immigrants from this country.

Immigration from Ethiopia

Ethiopian Jewry was in contact with European Jewry as early as the 19th century, and the Jewish community in Ethiopia, known as Beta Yisrael, dreamed of and prayed for aliya to Israel for hundreds of years.

In the 1970s, a regulation was published which was intended to make it difficult for Beta Yisrael Jews to enter Israel and immigrate to it, and Israel even began expelling Ethiopian Jews who had managed to immigrate to Israel up to that time. Activists on behalf of the immigrants, who had to go underground to avoid expulsion, turned to Rabbi Ovadia Yosef, who ruled that Ethiopian Jews were Jews for all intents and purposes. Even so, the Interior Ministry refused to change its policy. In 1977, after many political upheavals, the Interior Minister at the time, Shlomo Hallel, officially applied the Law of Return to Ethiopian Jews.

Over the years, Ethiopian Jews have been brought to Israel in a series of operations, including Operation Moses and Operation Solomon, and members of the Beta Yisrael community have received legal status under the Law of Return.

Yet, a large portion of the immigrants from Ethiopia are from the Falash Mura, to whom the Law of Return never applied. The Falash Mura are descendants of Jews from several generations ago, who were involved with the Jewish community to some extent and persecuted by Ethiopian Christians for their Jewish background. The Falash Mura do not immigrate to Israel under the Law of Return, but rather under various government decisions which set various criteria for their aliya to Israel. Their aliya was permitted in accordance with lists in which the families were registered with the number of members in each family.

These records caused many problems, since members of the Falash Mura often waited many years to immigrate to Israel. As a result, for example, new children were born who were not on the original family lists, etc. Many of the Falash Mura were forced to undergo a full conversion to Judaism.

When the Falash Mura began immigrating to Israel, the state even denied them oleh certificates and the accompanying rights, claiming that they converted in Israel and therefore did not deserve the rights. The Supreme Court put an end to this policy in the framework of the Ichobdink case, and ruled that the Falash Mura should receive oleh status as soon as they converted.

Aliya from Ethiopia, therefore, is a complex matter which requires significant familiarity with the various government decisions on the issue, and it is recommended to obtain legal counsel from an expert attorney regarding any question on this subject.

What can be done if your application for aliya is rejected?

First of all, it is important to understand that many times, before issuing a rejection, an unofficial policy of delay is employed – that is, additional requests for more documents, and lack of response to the application for a very long period, sometimes even for years. This tactic is common for aliya applications that the authorities intend to reject, and is often very effective, causing some aliya applicants to eventually give up and abandon their application.

Yet, many times, before an actual rejection is obtained, it is necessary to get a court to order the Interior Ministry to issue a decision on an aliya application that has been delayed for months or even years. Sometimes after submitting such a request, oleh status is approved without need for an additional application to the court. However, in other cases, such a request is followed by a rejection.

Rejection of an aliya application cannot be directly appealed in the courtsl an internal appeal must first be submitted to the Population and Immigration Authority. This process is done in the framework of what is known as “exhaustion of proceedings”: an expression from administrative law, which obligates anyone who wants to appeal a decision by an authority to do everything possible within that authority before turning to the court.

If a second rejection is issued after submitting a detailed, reasoned internal appeal, the applicant may appeal to the court.

Up to 2019, the authority to hear aliya cases was granted to the Supreme Court, but after an amendment to the law, the authority is presently in the hands of the Administrative Affairs Courts, which are district courts. An appeal to the Administrative Affairs Court for an aliya case must be submitted by an attorney specializing in the field. It is important that the appeal be based on what was written in the internal appeal, and therefore in any case of an aliya application being rejected or unreasonably delayed, it is important to seek legal counsel and assistance from an attorney specializing in this area.

Summary

Immigration to Israel began with a simple, short law intended to realize the dream of ingathering of the exiles. The state’s founders sought to make Israel into a refuge for Jews from all over the world. However, this law has undergone many transformations during the years that the State of Israel has been in existence.

At present, this right is anchored in many regulations and significant bureaucracy, which changes from one immigrant to another, but still allows Jews and family members of Jews to immigrate to Israel and obtain immediate rights as citizens. This right is based solely on the applicant’s Jewishness or his familial connection to Jews.

Yet, there are more than a few challenges facing aliya applicants, described in detail in this article, of which a potential applicant should be aware. Therefore, to undergo the process in the best possible manner and avoid snags, it is important to consult with an attorney who is familiar with the details of the process and of the law, before submitting the aliya application.

- The Law of Return

- Aliya before the founding of Israel